Germany's Reluctance To Accept European Commission Decisions Concerning The Adequacy Of The Level Of Data Protection In Non-EU/EEA Countries

Article by Prof. Dr. Michael Schmidl, LL.M. Eur. (Rechtsanwalt/Maître en Droit), published by BNA International in World Data Protection Report 02/2011, p. 1 - 4.

It is one of the basic mechanisms of the German Federal Data Protection Act (‘‘FDPA’’) to require a statutory permission or a declaration of consent for the collection, processing (which includes storing and transferring) and use of personal data. No permission is needed, however, for exchanging personal data with a data processor in Germany, the European Union or the European Economic Area (‘‘EU/EEA’’) and for having it carry out processing operations, it being understood that the parent company, a company of the same group of companies or an external service provider can be used as data processors. Should such a data processor be located outside the EU/EEA, the FDPA qualifies the exchange of personal data with the processor as a ‘‘normal’’ data transfer and the aforementioned rule applies again.

You can also download a PDF version of this article.

This means that a statutory permission or the data subjects’ consent is needed in order to legitimize the data exchange, which has ‘‘turned into’’ a data transfer solely as a consequence of the data processor having its seat outside the EU/EEA. While consent is difficult to obtain and its validity is disputed in the employment relationship, statutory permissions also are hard to find, especially when it comes to the processing of special categories of personal data (information on racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, health or sex life).

There are many questions one could ask about this mechanism, for example, whether it makes sense to treat data exchanges between a controller and a non-EU/EEA data processor as ‘‘transfers’’, although the relationship between them is fully dominated by the controller’s instructions and a transfer is normally taking place between controller 1 and controller 2 as a means of empowering the latter to take his own decisions.

This article, however, focuses in Part I on the fact that the FDPA extends its restrictive handling of data transfers to data exchanges with data processors located in countries with an adequate level of data protection (‘‘adequacy state’’), according to a corresponding decision of the European Commission (‘‘adequacy finding’’) pursuant to Article 25 (6) of Directive 95/46/EC (‘‘EC Data Protection Directive’’). In Part II, the article shows the surprising unwillingness of the German legislator to eliminate the problem, despite concrete suggestions having been submitted by the German Federal Council and the serious consequences for German companies.

I. Data Processing in Adequacy States — EU and German Law

1. Adequacy Findings by the European Commission

The EC Data Protection Directive contains a clear concept regarding the transfer of personal data to recipients outside the EU/EEA, which can be illustrated by its Recitals 56 and 57 (emphasis added):

(56) Whereas cross-border flows of personal data are necessary to the expansion of international trade; whereas the protection of individuals guaranteed in the Community by this Directive does not stand in the way of transfers of personal data to third countries which ensure an adequate level of protection; whereas the adequacy of the level of protection afforded by a third country must be assessed in the light of all the circumstances surrounding the transfer operation or set of transfer operations;

(57) Whereas, on the other hand, the transfer of personal data to a third country which does not ensure an adequate level of protection must be prohibited;

While the use of Safe Harbor, model contracts and binding corporate rules creates an adequate level of data protection only on the level of the participating or contractually bound parties, an adequacy finding according to Article 25 (6) of the EC Data Protection Directive covers all recipients located in an adequacy state. Article 25 (6) reads as follows:

The Commission may find, in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article 31 (2), that a third country ensures an adequate level of protection within the meaning of paragraph 2 of this Article, by reason of its domestic law or of the international commitments it has entered into, particularly upon conclusion of the negotiations referred to in paragraph 5, for the protection of the private lives and basic freedoms and rights of individuals. Member States shall take the measures necessary to comply with the Commission’s decision.

The Member States’ obligation to respect an adequacy finding ensues from Article 25 (6) 2nd sentence of the EC Data Protection Directive and from Article 4 (3) of the EU Treaty. Article 4 (3) contains the ‘‘duty of loyal cooperation’’. This principle shall ensure that Member States interpret and implement EU legislation in a uniform way, allowing it to take its intended effect. The intended effect of an adequacy finding is to allow ‘‘crossborder flows of personal data’’ (see Recital 56 above). In other words, the Member States have to treat data processors located in adequacy states the same way as data processors located within the EU/EEA.

2. Effect of Adequacy Findings with Regard to Data Processing under German Law

German law, more precisely the FDPA, completely ignores adequacy findings by requiring that German controllers also fulfill the requirements of a veritable data transfer for exchanging data with data processors in adequacy states.

Technically, this discrimination of data processors in adequacy states is reached by Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA, which qualifies data processors located in adequacy states as ‘‘third parties’’, thus fulfilling the definition criteria of a veritable transfer, while this is not the case for data processors located in the EU/EEA. A data exchange with such data processors is no ‘‘transfer’’, since they are exempted from being a ‘‘third party’’. However, a data transfer is possible according to Section 3 (4) No. 3 FDPA only if the ‘‘disclosure of personal data to a third party’’ occurs. Section 3 (8) FDPA reads as follows (emphasis added):

‘‘Recipient’’ means any person or body receiving data. ‘‘Third party’’ means any person or body other than the controller. This shall not include the data subject or persons and bodies commissioned to collect, process or use personal data in Germany, in another member state of the European Union or in another state party to the Agreement on the European Economic Area.

The consequence of the non-exemption of data processors in adequacy states from the quality of ‘‘third party’’ is that, according to Section 4 (1) FDPA, exchanging personal data with them is permissible only if the data subjects have given their consent or there is statutory permission. With regard to ‘‘normal’’ personal data, the transfer requirements are sometimes hard to meet. With regard to special categories of personal data defined in Section 3 (9) FDPA, the statutory requirements imposed by the FDPA can hardly be met. The only way to use a data processor in an adequacy state would be to obtain the data subjects’ consent. Obtaining the data subjects’ consent is not only impractical; its effectiveness is even doubted in an employment relationship (where the implementation of data processors is very common) in light of the employees’ (potentially) limited possibility to take a free decision.

By treating data processors located in adequacy states differently than data processors located within the EU/EEA by means of Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA, Germany violates the obligations ensuing from Article 25 (6) 2nd sentence of the EC Data Protection Directive and from Article 4 (3) of the EU Treaty. Moreover, from the point of view of constitutional law, it may well be asked how the differentiation between a data processor in the EU/EEA (i.e., in an area with an adequate level of data protection), on the one side, and a data processor in an adequacy state (i.e., in an area with an adequate level of data protection), on the other, can be justified. Article 3 of the German Constitution requires that equal constellations have to be treated the same way. The current wording of Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA is therefore also in breach of Article 3 of the German Constitution.

II. The German Government’s Unwillingness to Solve the Problem and the Consequences

1. The German Federal Council’s Attempt to Cure the Breach of EU Law

The German Federal Council recognized the violation of EU law by Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA, and on November 5, 2010 (BR-Drucks. 535/2/10) suggested the following changes (see the italicized parts) to the wording of Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA in the current legislative procedure on a bill on employee data protection (see analysis by Michael Schmidl and Benjamin Baeuerle, of Baker & McKenzie, Munich, at WDPR, September 2010, page 28):

‘‘Recipient’’ means any person or body receiving data. ‘‘Third party’’ means any person or body other than the controller. This shall not include the data subject or persons and bodies commissioned to collect, process or use personal data

1. in Germany,

2. in another member state of the European Union,

3. in another state party to the Agreement on the European Economic Area or

4. in a third country that ensures an adequate level of protection according to the Decision of the European Commission pursuant to Article 25 (6) of Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data.

The German government, however, based on the following reasons, refused the suggested changes in a statement dated December 15, 2010 (BT-Drucks. 17/4230):

The German Federal Government does not agree with the suggestion.

The suggested changes would not only cover employee data but would affect the FDPA in general. Such a change would be linked to a rule for the transfer of personal data in affiliated companies. Such rule requires a further in-depth assessment [. . .]. The current legislative procedure is therefore not suitable to introduce such far-reaching regulations. Furthermore the Commission itself takes the view that the requirements for the finding of the Commission that a third country ensures an adequate level of data protection are not sufficiently specified in the European Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC (see Communication from the Commission dated 4 November 2010 on ‘‘A comprehensive approach on personal data protection in the European Union’’, COM(2010) 609 final, Number 2.4).

Neither of these reasons is convincing, as explained below.

The first reason given by the government is: ‘‘The suggested changes would not only cover employee data but would affect the FDPA in general. Such a change would be linked to a rule for the transfer of personal data in affiliated companies. Such rule requires a further indepth assessment’’.

This reason is not convincing because data processing is a generic phenomenon and is, of course, not limited to the employment relationship, where it is usually found in the context of a group-wide shared IT infrastructure. Therefore, there is no doubt that the suggested changes would affect employee data, personal data of other data subjects and also affiliated companies. However, because data processing is a generic phenomenon, a suggestion must not be rejected because it solves the problem not only for employee data. It is necessary to come to a solution that goes beyond the protection of employee data and solves the problem in its entirety, thus also putting an end to the violation of EU law. No in-depth assessment is necessary to come to this conclusion.

The second reason given by the government is: ‘‘Furthermore the Commission itself takes the view that the requirements for the finding of the Commission that a third country ensures an adequate level of data protection are not sufficiently specified in the European Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC [. . .]’’.

This reason is not convincing, either. The Commission paper dated November 4, 2010, may in no way serve as a basis for the rejection of the suggested changes to Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA. It is true that the Communication states under Number 2.4 that it is intended to clarify the procedure used to come to an adequacy finding. However, nowhere in the Commission paper does the Commission question 1) its competence for adequacy findings pursuant to Article 25 (6) of the EC Data Protection Directive, 2) the applicability of the adequacy findings rendered up to now and 3) the continued existence of a procedure for rendering adequacy findings in the future. Therefore, nothing in the Commission paper gives reasonable cause for the German legislator not to respect the Commission’s existing adequacy findings.

2. Consequences for German Companies

The effects of the described situation are not limited to ‘‘merely’’ violating Germany’s legal obligations ensuing from Article 25 (6) 2nd sentence of the EC Data Protection Directive, from Article 4 (3) of the EU Treaty and from Article 3 of the German Constitution. In its present version, Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA also triggers significant economic disadvantages for German companies, which their EU competitors do not have to put up with.

The following three scenarios illustrate the economic and ensuing competitive disadvantages faced by German companies:

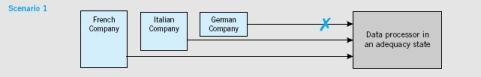

Scenario 1: A German company trying to use a data processor within the EU/EEA may do so without having the obligation to meet the requirements the FDPA imposes on the transfer of personal data (see I. 2. above). This is not the case for a German company trying to use a data processor located in an adequacy state. In light of the clear guidance by statutory German law, there is no interpretation that would lead to allowing the data processing of special types of personal data in an adequacy state (e.g., Switzerland), a unique situation in Europe (see Scenario 1 chart).

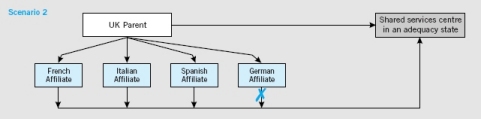

Scenario 2: Furthermore, a German company is cut off from any attempt of a parent company centralizing the processing of personal data (e.g., by a shared IT infrastructure) for its European affiliates in an adequacy state (see Scenario 2 chart).

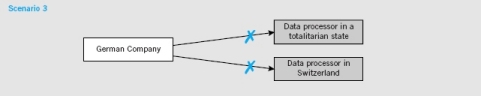

Scenario 3: The legal incorrectness of Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA is particularly obvious when considering that German data protection law treats data processors located in adequacy states, like Switzerland, the same way as data processors located in totalitarian states where human rights are not respected (see Scenario 3 chart).

Conclusion and Outlook

It is good news that German politicians have finally addressed the obvious problem resulting from the current wording of Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA. This also applies to the German government, which has not raised any arguments against the idea as such of changing Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA.

Rather, the German government seems to have strategic reasons for not accepting the Federal Council’s suggestion. It is probably correct to interpret the German government’s answer as a ‘‘yes, but not now’’. Even though it is positive that everybody is in agreement regarding the problem, it is wrong to wait for better occasions to cure it. The current legislative procedure on a bill on employee data protection offers a good opportunity to correct Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA.

It can no longer be expected that German companies should abide by Section 3 (8) 3rd sentence FDPA despite the fact that it obviously violates EU law, thus forcing them to invest in their own IT infrastructure, instead of using a specialized data processor or sharing the IT infrastructure established by the parent company or an affiliate in an adequacy state.